The Majesty of Maps

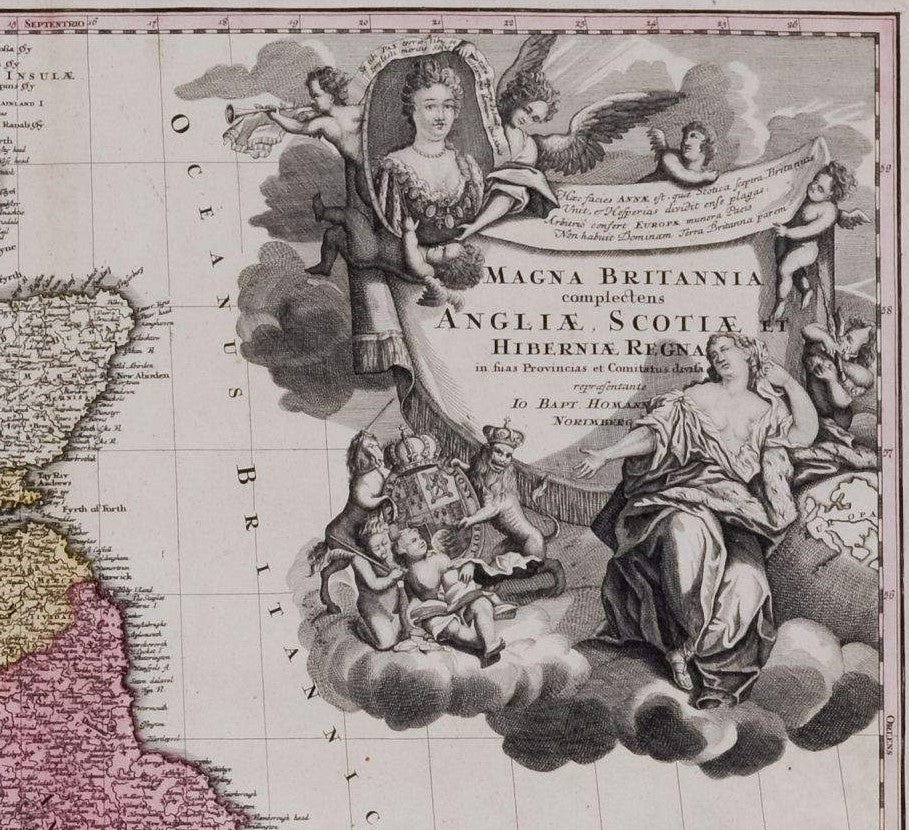

Kings, Queens, Emperors and assorted scions of royal houses make frequent appearances on decorative maps. Sometimes it’s all to do with the dedication: one of the most elaborate examples which comes to mind is the scene depicting map-maker John Ogilby kneeling before Charles II and Catherine of Braganza, presenting the King with the subscription book for his great map of London, which was eventually published by his step-nephew William Morgan in 1682. Portraits are not necessarily patriotic or flattering, especially when maps were published overseas. Johann Baptist Homann’s map of Great Britain was engraved in Nuremberg c. 1707 with a portrait of Queen Anne, which was updated with portraits of the first two Georges, as and when it became appropriate.

Mehmed had been dead for well over a century, but I reasoned that the fall of Constantinople still reverberated in the west, and Hondius could have calculated that his face would sell more maps than either the current Ottoman Emperor or an allegorical scene depicting stock characters, such as Christian captives, fierce Janissaries or a stylised ‘Emperor’ figure. However, I stand corrected. My friend and colleague Angus O’Neill tracked down the portrait which is unquestionably the one which Hondius copied: the pose and even the jewels are the same. Now in the Topkapi Palace, it portrays Mehmed III who died in 1603, shortly before Hondius bought the Mercator copper printing-plates and began work on his own edition of the atlas. Bellini wasn’t the only foreigner commissioned to paint a sultan, and portraits (and copies of portraits) did circulate in the west: there were especially strong artistic links between Constantinople and Venice. Hondius was presumably aware of Mehmed III’s death, and the accession of his successor Ahmed I, but did not have an up-to-the-minute portrait of the reigning sultan. The portraiture time-lag wasn’t a century though.

John Speed’s purposes were slightly different. The maps in his atlas of the British Isles (like Hondius’ map of the Turkish Empire), were current maps, but they could also be used to illustrate Speed’s history of Britain, and they contain a wealth of historical detail. One of Speed’s most decorative county maps is his map of Lancashire, featuring fine medallion portraits of ‘all those kings sprunge from the royal families of Lancaster [on the left] and Yorke [on the right] which with variable success got and enjoyed the Crown and kingdom’. The Wars of the Roses, which began in the reign of Henry VI (top left) petered out after Richard III was killed by Henry VII’s forces at Bosworth in 1485. The threat of a Yorkist uprising persisted into the reign of Henry VIII, and when Speed’s map was engraved in 1610 less than a decade had elapsed since the death of Elizabeth I, last of the Tudor monarchs. It was history, but very recent history, which accounts for Speed’s careful turn of phrase (‘variable success’ is a delightful summary of decades of bloody civil war). The portraits and decorative strap work around them are entirely symmetrical and evenly balanced. Again, perhaps this would only have become possible under the Stuarts. Shakespeare was Speed’s contemporary, and the history plays which he wrote under Elizabeth - including ‘Richard III’ (1593) - are seldom nuanced. Speed’s Lancashire might have looked rather different if he had begun work on it a decade earlier. As it is, the quotation from Matthew 5:9 which appears above the Lancastrians, ‘blessed are the peacemakers’, makes it clear - just for safety’s sake - that Speed’s official allegiance was to the winning side.

Speed illustrated the royal family of his own day, the newly installed Stuart dynasty, on his map of Scotland. The portraits in the borders originally represented James VI and I, his wife and children - including a young Prince Charles. The printing plate was not revised when Charles became King; a generation of publishers was content to allow the portraits to become historical, but that all changed after Charles was beheaded in 1649, and printing royalist imagery in England (however outdated) was likely to attract unwelcome attention. The royal family was burnished from the copper plate during the Interregnum and replaced with the ‘commoners’ seen here: a ‘Scotch’ man and woman, and a ‘Highland’ man and woman (notable, I’m told, as early depictions of tartan - possibly the first in print). The map continued to be printed long after the Restoration, but no attempt was made to restore the royals – Scotland remained egalitarian.

As Bavaria was allied with France during the War of the Spanish Succession, against Anne’s England, the best one might reasonably expect is a neutral portrait, an identification of monarch with nation; under the circumstances the result is quite flattering.

It set me thinking about the presentation of deceased rulers on maps. Given the tensions between western Europe and the Ottoman world, the depiction of Turks on printed European maps is often skewed, and more often than not allegorical. For his new map of the Ottoman Empire, however, Jodocus Hondius chose to use the portrait of a figure identified as ‘Sultan Mahumet Turcorum Imperat’ – which I thought was probably Sultan Mehmed II, ‘the Conqueror’.

Mehmed had been dead for well over a century, but I reasoned that the fall of Constantinople still reverberated in the west, and Hondius could have calculated that his face would sell more maps than either the current Ottoman Emperor or an allegorical scene depicting stock characters, such as Christian captives, fierce Janissaries or a stylised ‘Emperor’ figure. However, I stand corrected. My friend and colleague Angus O’Neill tracked down the portrait which is unquestionably the one which Hondius copied: the pose and even the jewels are the same. Now in the Topkapi Palace, it portrays Mehmed III who died in 1603, shortly before Hondius bought the Mercator copper printing-plates and began work on his own edition of the atlas. Bellini wasn’t the only foreigner commissioned to paint a sultan, and portraits (and copies of portraits) did circulate in the west: there were especially strong artistic links between Constantinople and Venice. Hondius was presumably aware of Mehmed III’s death, and the accession of his successor Ahmed I, but did not have an up-to-the-minute portrait of the reigning sultan. The portraiture time-lag wasn’t a century though.

John Speed’s purposes were slightly different. The maps in his atlas of the British Isles (like Hondius’ map of the Turkish Empire), were current maps, but they could also be used to illustrate Speed’s history of Britain, and they contain a wealth of historical detail. One of Speed’s most decorative county maps is his map of Lancashire, featuring fine medallion portraits of ‘all those kings sprunge from the royal families of Lancaster [on the left] and Yorke [on the right] which with variable success got and enjoyed the Crown and kingdom’. The Wars of the Roses, which began in the reign of Henry VI (top left) petered out after Richard III was killed by Henry VII’s forces at Bosworth in 1485. The threat of a Yorkist uprising persisted into the reign of Henry VIII, and when Speed’s map was engraved in 1610 less than a decade had elapsed since the death of Elizabeth I, last of the Tudor monarchs. It was history, but very recent history, which accounts for Speed’s careful turn of phrase (‘variable success’ is a delightful summary of decades of bloody civil war). The portraits and decorative strap work around them are entirely symmetrical and evenly balanced. Again, perhaps this would only have become possible under the Stuarts. Shakespeare was Speed’s contemporary, and the history plays which he wrote under Elizabeth - including ‘Richard III’ (1593) - are seldom nuanced. Speed’s Lancashire might have looked rather different if he had begun work on it a decade earlier. As it is, the quotation from Matthew 5:9 which appears above the Lancastrians, ‘blessed are the peacemakers’, makes it clear - just for safety’s sake - that Speed’s official allegiance was to the winning side.

Speed illustrated the royal family of his own day, the newly installed Stuart dynasty, on his map of Scotland. The portraits in the borders originally represented James VI and I, his wife and children - including a young Prince Charles. The printing plate was not revised when Charles became King; a generation of publishers was content to allow the portraits to become historical, but that all changed after Charles was beheaded in 1649, and printing royalist imagery in England (however outdated) was likely to attract unwelcome attention. The royal family was burnished from the copper plate during the Interregnum and replaced with the ‘commoners’ seen here: a ‘Scotch’ man and woman, and a ‘Highland’ man and woman (notable, I’m told, as early depictions of tartan - possibly the first in print). The map continued to be printed long after the Restoration, but no attempt was made to restore the royals – Scotland remained egalitarian.

Leave a comment