How To Read Maps: Blind Date

Maps which were published in atlases or travel books are frequently (though not always) undated: the date was on the title-page. Sometimes the edition can be ascertained by changes made to the map itself, or by the setting of the letterpress (the text above or below the map, or on the verso). Now and again a page or volume number has been engraved which shows where the plate should have been bound in a particular edition, as is the case with the ward plans which illustrated 18th century editions of Stow's Survey of London, edited by John Strype.

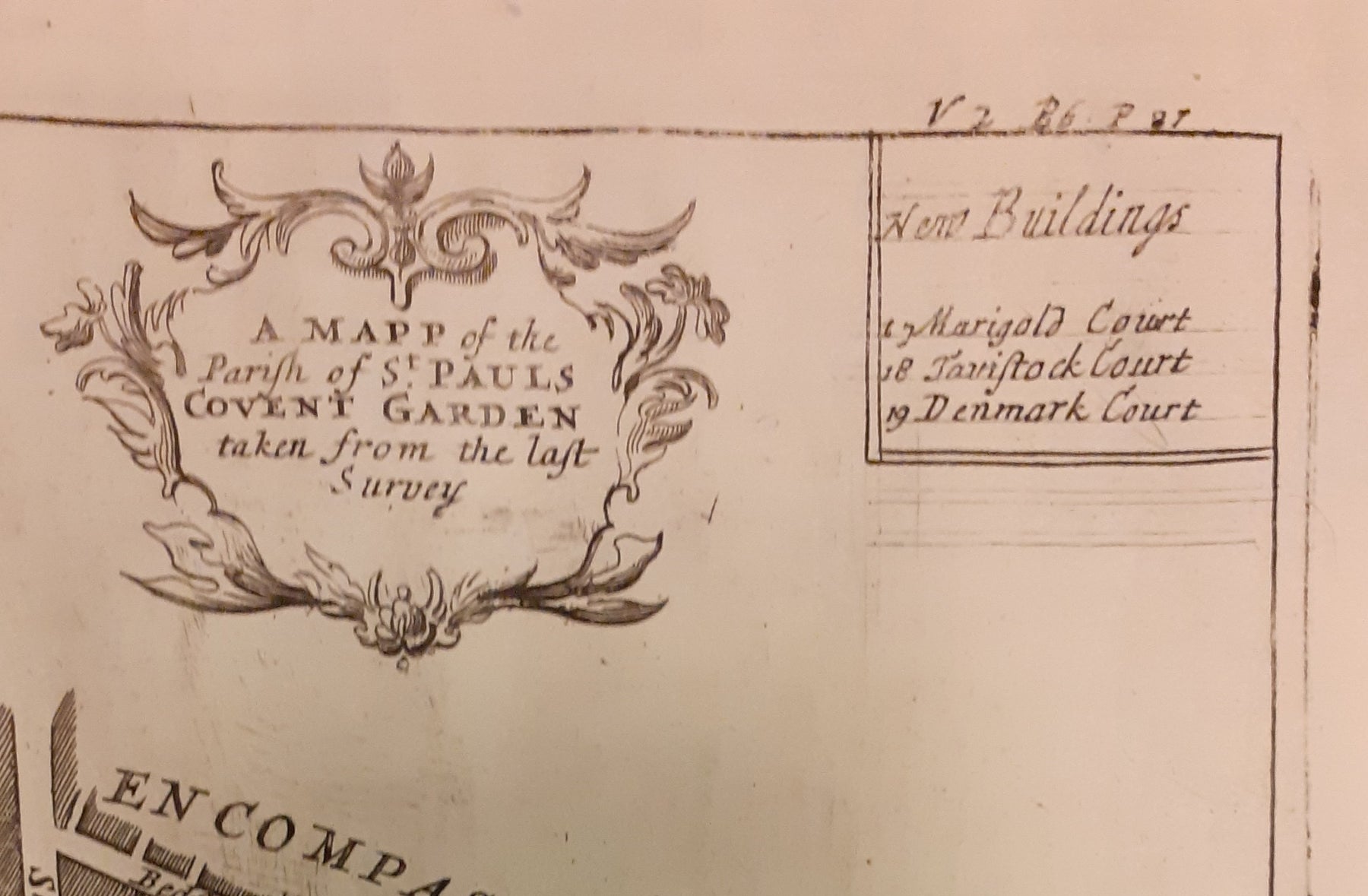

The page and volume number indicates that this map was published in the 1720 edition of Stow’s Survey; the imprint (but not the cartography) was revised for the 1755 edition. As an extra clue the guide rules can still be seen here: guide rules were lines which were faintly incised on the plate to help the engraver align the lettering (all freehand, and back to front). It was done lightly, and they were expected to wear away after the first few impressions had been taken.

The guide rules are even clearer in this detail from the map of the parish of St Paul’s, Covent Garden, from the same edition.

But, in case this all sounds too easy, dates which do appear on maps in books often relate to when the map was engraved rather than when that particular map was printed. John Speed's county maps provide a classic example. Mostly engraved around 1610 and dated accordingly, the dates were seldom revised or removed even though the copper plates survived - and were printed from - for well over a century. Dating is achieved through a combination of changes made to the plate, the setting of the text on the verso, and publishers' imprints: the plates changed hands several times and the new owners mostly put their names on the map.

This copy of Speed's Berkshire is bound into Elias Ashmole's history of Berkshire, published in 1719, which ought to give the game away, but it is an extra illustration (not called for in the collation) and it is still useful to demonstrate that it was a newly printed in 1719; it wasn't an old map bound in on the whim of an early owner. The first clue is that the other map in the book - Hollar's Berkshire, which is supposed to be there - was supplied by the same publisher. But if our Speed was loose it would still be possible to demonstrate that it was printed a hundred years after the first edition. Two extra coats of arms were added for the 1676 Bassett and Chiswell edition; their successor Christopher Browne made no changes, but on his retirement c. 1713 the plates were bought by Henry Overton. Overton added his own imprint (although he didn't bother to burnish out Bassett and Chiswells', which can still be seen at the bottom of the the map) and he updated the map by adding the major roads (bringing them into line with other county maps published after the appearance of John Ogilby's innovative road book in 1675, such as Robert Morden's series of counties engraved for a new edition of Camden in the 1690s). A clincher is the outline hand colour. Very few early Speeds were coloured at the time, but after a hundred years of hard use (it was the most popular county atlas of the 17th century, and every single copy of the map in existence was pulled from the same piece of engraved metal) the plates were somewhat worn: the colour compensated for the weakness of the impression.

If that gives a flavour of dating maps which appeared in books, dating separately published maps can be even more of a minefield. Let's start with a map which does have a date on it, 'Wallis's Tour Through England and Wales, A New Geographical Pastime', one of a number of Georgian tabletop games we've been playing recently.

John Wallis's imprint is dated December 24th 1794. I don't believe every date I see on a map, and in this case I don't think Wallis or his apprentices were labouring, Cratchit like, to get this finished on Christmas Eve – although I do think it may have been intended for the Christmas market. However, Wallis didn't quite get it ready in time: the it’s a race game in which players learn about towns and cities as they land on them, and the most recent date in the text relates to number 105, Harwich; it’s close to the finish of the game in London (117) but it hasn’t been squeezed in for a later edition. It refers to the arrival of William V, the last Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, who fled the French invasion of the Netherlands in January 1795. Publication may therefore have been slightly delayed, but in any case our example seems to have been sold some years later. The printed label on the slipcase – which fits the map snugly – is dated 1802. Wallis did reissue this game in 1802, and our example is probably an instance of Wallis using up old stock with the new slipcase.

One can also use provenance or marks of ownership to help establish a date, although just because someone wrote a date or bought a map at a particular time – even if 'new' – does not prove that the map had only just been published. As with Wallis' game above, there could be a lag of several years.

We currently have an example of Faden's map of Europe which is dated 1791, and one Colonel Cheney of the 1st Guards has written his name on the slipcase and on the back of the map, to make sure absolutely no-one else could walk off with it by mistake. While a Colonel, he became an ADC to George III - a keen map collector with a habit of filleting state papers for any cartographic content - so writing his name clearly may have been a wise move, but it also helps us pin down when he bought it. Robert Cheney (1766-1820) served in the 1st Foot Guards throughout his career, but only rose to the rank of Colonel in 1805. It makes sense that he purchased the map around that time: a general map of Europe would have been of far more use for an ADC to the King than for an officer on campaign in the Peninsula, which is where his military service led next. And there's no reason to think he bought it secondhand. But it's easy to see from this example how an engraved date or handwritten provenance, without other supporting evidence, can easily throw out the date of when a map entered circulation by a decade or more.

When we haven't got a printed date or helpful ownership signatures, we have to start looking for internal dating evidence. It's especially tricky when a map is previously unrecorded, and nobody else has done the work already. Here's a scarce map by John Luffman:

Maps by the author, bookseller and map-maker John Luffman (1751-1821) are relatively unusual. He endured bankruptcy in 1793, and although he was able to re-establish himself, he confined his activities to smaller educational and topical maps, such as this one. A handful of similar (but not identical) maps by Luffman are held by institutions around the world, dated 1807-1812. Some are dated, perhaps to make them seem up to the minute; some are not, perhaps to extend their shelf life. With no date to go on here, the first port of call is the address in Luffman's imprint, but as he stayed in the same place between 1807 and 1820 it doesn't help us much - this time. However, our map shows Napoleon’s 1812 invasion route to Moscow, so it can't be any earlier. And it doesn't show the line of his retreat. It's not a given that Luffman would have updated the map, but it's certainly reasonable to date the map to 1812-13 when the 'seat of war' between Russia and France covered this ground, and was of vital importance.

If there is no date, no publisher and no indication of who the map was made for, things can start to get tricky. As an example, we currently have a 40 x 60 inch poster map, made for display in an Edwardian London Underground station. Who made it and why would have been perfectly obvious in its original context, and in the normal way of things it would have been torn down or pasted over a few months later. No other copies are currently known to have survived, and the original makers weren't to know that they would have caused quite so much head scratching over one hundred years later.

We know it was made for display in stations, but establishing which ones presents a challenge. We can date it with reasonable confidence to 1906, or perhaps a fraction earlier. Our map predates the western extension of the Central London Railway to Wood Lane, which opened for the Franco-British Exhibition in 1908. Angel is still shown as the terminus of the City & South London Railway, but the western extension to Euston, which opened in May 1907, is under construction. The use of a green border appears to be a nod to the successful series of green-bordered UERL (Underground Group) maps, but as those were introduced in 1907 it might be the other way around. Another unusual design feature is the two tone shading (in line colours) of the names of interchange stations, such as ‘The Bank’. The Bakerloo Line, which opened in March 1906, appears to be shown as a thin dotted black line, but as it was owned by the rival UERL its use for dating purposes cannot be guaranteed: this is most emphatically not a UERL map. Just three underground lines are highlighted, none of which was under the UERL umbrella in 1906: The Central London Railway, the City & South London Railway and the Great Northern & City Railway (the first two purchased by the UERL and the latter by the Metropolitan Railway, all in 1913). Two mainline companies are featured: the Great Northern Railway with its terminus at Finsbury Park and the Great Western Railway, which served Paddington. Of these two, the GWR is far more prominent, with an inset showing the route to Reading. The map promotes travel across London using the highlighted routes at the expense of all others, including the UERL: all are razor thin, black and unobtrusive with no further differentiation between underground, mainline and suburban services, and seemingly haphazard naming of stations. It seems likely that our map was a joint response by three of the independent underground railway companies to the growing power of the UERL, possibly in co-operation with the GWR, and was created for display in any of their stations.

Hopefully these examples will be of some use for any readers with a dating quandary of a cartographic nature. Let them also serve as a warning: before you ask, ever so casually, how do we know the date of a particular map, how far down the rabbit hole do you want to go? It might be a short hop or we might go all round the warren… do you feel lucky?

Leave a comment