Noble Seats & How To Spot Them

This sounds niche, I know, but the depiction of great estates is a distinctive and prominent feature of English county cartography. Look at comparable early maps of, say, French provinces and they aren’t to be seen. The tradition began with the earliest printed county maps by Christopher Saxton, published in the 1570s. John Norden followed his example in the 1590s, and in the first decade of the 17th century so did Williams Smith, Kip and Hole and John Speed. When the major continental map publishers got in on the act in the 1630s, the precedent was well established in their English source material and they copied it.

What map-makers choose to include (or not) says a great deal about the values and priorities of contemporary society. These early maps were produced in a society obsessed by order and degree, its balance maintained (or so many educated people thought) by the celestial harmony of the music of the spheres, and where private consumption was regulated by strict sumptuary laws. In that context, the great estates were as much a part of the natural order as rivers, forests and mountains. None of these early modern map makers thought it necessary to show the roads; after all, travel was slow and hazardous, and travelling in any sort of comfort was expensive. In any case, way-finding was not the primary purpose here. Without roads and other features to clutter up the map, the estates stand out even more prominently: statements of ownership, supported by the coats of arms and other ‘decorative’ features of these maps which it is easy for the modern reader to dismiss as frivolous.

In fairness, the great estates were major features in the landscape. They were typically irregular in shape and surrounded by palings eight to ten feet high, which are represented pictorially on the maps. One suggestion is that this was to keep deer in, being higher than a deer can jump, but it was often more important to keep people out – particularly to protect mature timber, which was a major resource and source of income. A Tudor landowner would typically harvest timber planted in the time of his grandparents, and plant trees for his grandchildren: it spanned the generations. We’re only going to look at a handful of examples, but you can see at once that considerable care has been taken to define the sizes and shapes of the estates with reasonable accuracy and locate houses and wooded areas within them: they are not represented with standard symbols, like most towns and villages.

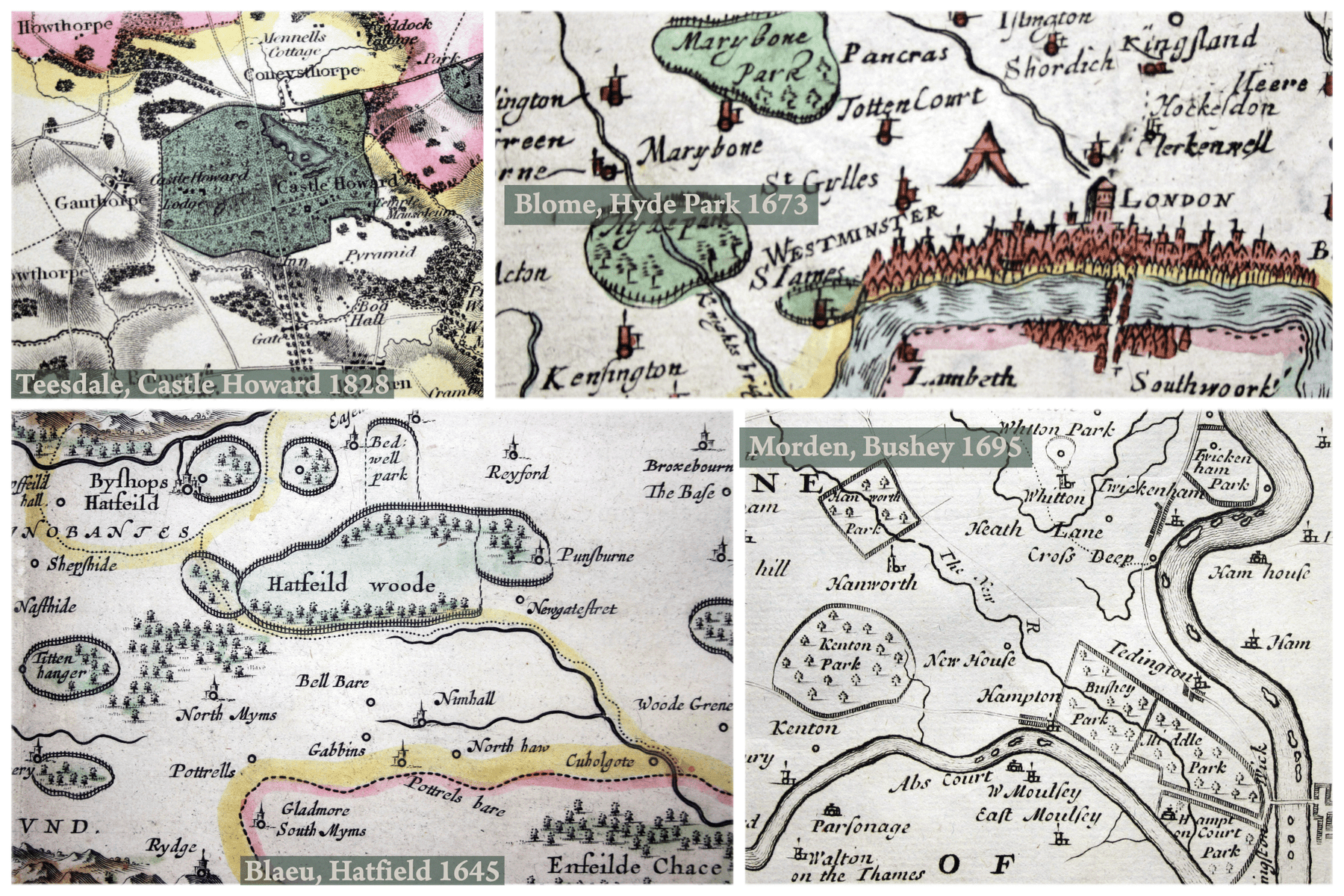

I thought we’d start with the family seat of the Cecil family, shown on this detail from a 1645 Blaeu map of Hertfordshire. Hatfield, or Bishop’s Hatfield as it then was, grew up by the gates to Hatfield House and the symbol denoting a significant town (larger than any of the surrounding villages) cuts into the estate boundary to suggest that relationship. Hatfield House itself is un-named but marked on the map, a simple open circle just to the east of the town. Just to the southwest is Tyttenhanger House and estate, then the seat of the Blount family. To the east are Essendon Place and Bedwell Park.

The three enclosed estates on this detail from Richard Blome’s 1673 map of Middlesex are all owned by the crown. All would now appear (at least in part) on a typical map of central London, but 350 years ago even St James’s Park was on the very fringe of the built up area. Marylebone Park, distant ancestor of Regent’s Park, had been acquired and enclosed by Henry VIII as a deer park (maybe the deer did matter more than the trees in this instance). Hyde Park, too, began life as one of Henry VIII’s hunting grounds, although it was opened to the general public by Charles I: astonishing that it was a well established place of recreation even when this map was printed. Note the pavilion, east of St Giles...

More royal residences and hunting grounds on this detail from Robert Morden’s 1695 map of Middlesex: Hampton Court, Bushy Park and Hanworth Park. The latter contained a Tudor hunting lodge, often referred to as a palace, and a lodge had been built in Bushy Park in 1683, but neither appears to have been substantial enough to be marked on the map as an individual building. Non royal residences include Twickenham Park, the former home Francis Bacon, and Whitton Park, a modest private estate enclosed in 1625 by one Henry Saunders. But enclosures are no longer dominating the landscape in quite the same way as before. Ham House is one of the private residences which are marked and named, but it was set in modest formal gardens rather than acres of parkland and no attempt is made to delineate estate boundaries. And there is more going on, which competes with the enclosures for attention. Inspired by John Ogilby’s pioneering road atlas, Morden was among the first to include the major roads on his county maps: where towns and villages (e.g. Twickenham) lie on the road he sketches in their layout, though he retains his symbol denoting ‘village’ to one side. These simple shaded areas represent the dwellings of ordinary people on a scale which starts to match the great estates.

This is Castle Howard on Henry Teesdale’s large-scale map of Yorkshire, published in 1828, amid a flurry of acrimonious correspondence about plagiarism with Yorkshire map-maker Christopher Greenwood. We are now in the Ordnance Survey era and on a map like this there is tremendous detail, down to the level of property boundaries and isolated individual buildings. Castle Howard still stands out. We see the tree-lined Avenue which is the main approach from the south, broken by a faux Gothic gatehouse designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor in the 1720s, with another of his follies, a pyramid, off to the right. In fact, we get an excellent idea of the house and grounds laid out by Vanbrugh and Hawksmoor, much of it neatly labelled. This is not just an exercise in garden history (although there’s nothing wrong with that): in an increasingly populous landscape this attention to detail confers power and prestige.

Teesdale’s map is dedicated to the nobility, gentry and clergy of Yorkshire. Creating new, large-scale surveys was prohibitively expensive, and selling them to wealthy people whose houses and estates appeared on the finished map was a significant part of the successful map-maker’s business model. Here is an 1802 edition of William Faden’s map of ‘the country twenty five miles round London’:

Again, it is aimed squarely at the carriage trade: all the splashes of green denote parks and estates occupied by the nobility, gentry and prosperous businessmen ringing the capital.

Just for fun, contrast Faden’s map with this map showing the newly created LPTB operating area in 1934. Made for public display rather than private purchase, most of the green spaces are public parks, golf courses and aerodromes. In the 20th century map readers became accustomed to associate ‘enclosures’ with leisure travel rather than with a ruling elite.

Leave a comment