How To Read Maps: Dedication, That's What You Need

Set among the scales and cartouches and other decorative features on many early maps there is often a coat of arms and a panel of text extolling the titles and achievements of a particular individual; someone who was alive when the map was engraved, someone who was chosen by the map-maker to be the dedicatee of that particular map. Sometimes the same dedicatee appeared on editions of the same map for decades, long after both the original map-maker and the dedicatee were dead; sometimes the dedication was burnished from the copper printing plate and replaced with another, either because the original dedicatee had fallen from grace or because the map was updated more generally. Either way, it’s easy to skate over the dedication as a bit of puff, but dedicatees were chosen with care, and investigating who is on the map and why they are there can prove revealing about the circles in which map-makers moved, and who they were trying to impress.

Many early maps are individually dedicated. The author of (say) a novel usually got one crack at dedicating their book to someone significant or influential (for example, take Jane Austen’s dedication of ‘Emma’ to the Prince Regent, whom she loathed), but an atlas maker could curry favour on almost every page. Dedications usually appear with the subject’s consent. As with lists of subscribers the ideal (from a sales perspective) was endorsement from someone royal, or from the highest ranks of the aristocracy. If things went according to plan other people would clamour to be associated with the book and sales would rocket.

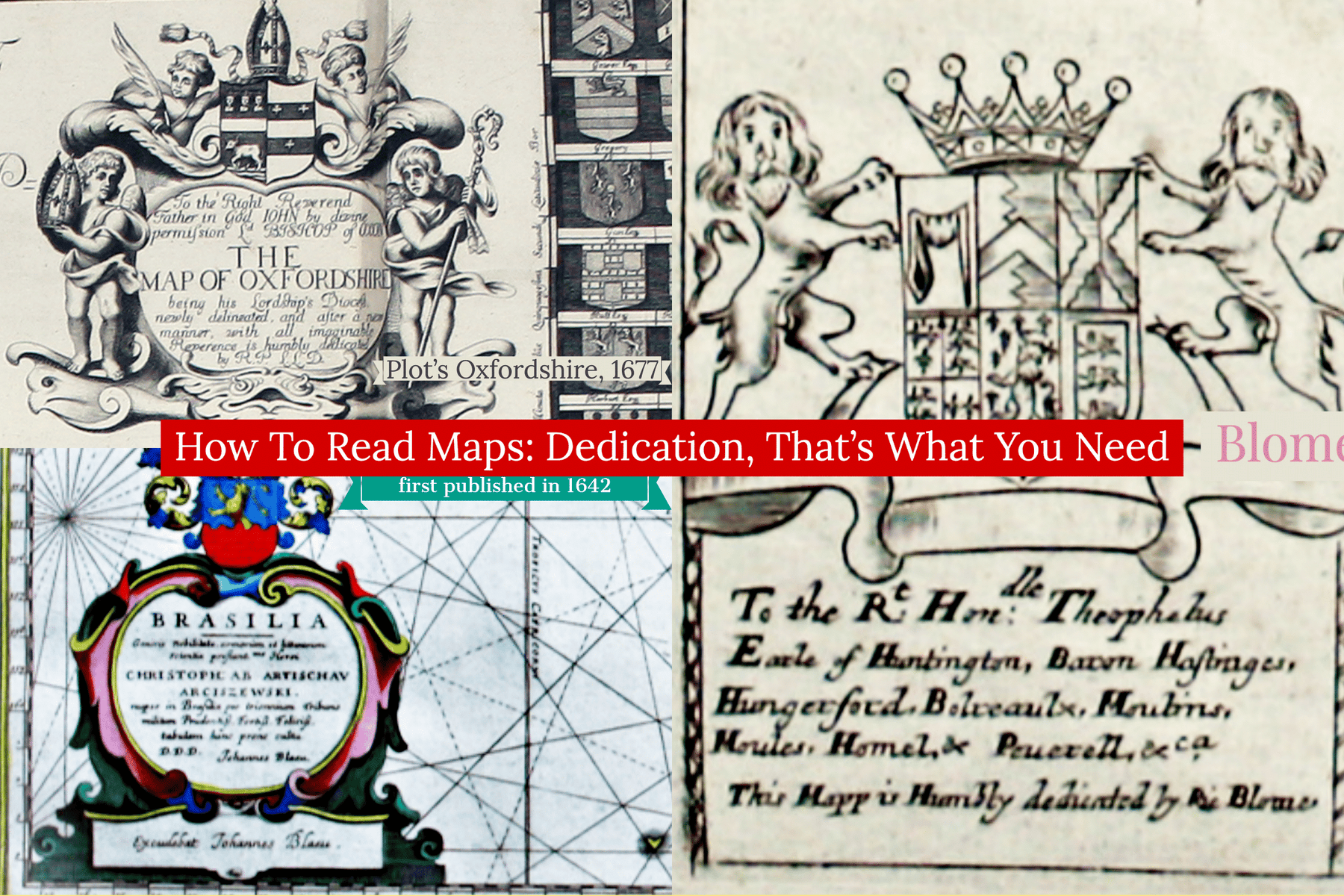

This was the policy adopted by Richard Blome in his ‘Britannia’ of 1673, the first new atlas of county maps published in Britain in the sixty years since the appearance of John Speed’s ‘Theatre’. The book was dedicated to King Charles II, as was the general map of the British Isles, leaving Blome with the rest of the atlas to play with. In the straightened financial environment of post-Restoration London, Blome was forced to rely on innovative funding sources: he was one of the first publishers of illustrated books to rely heavily on subscriptions, and subscribers to the Britannia were entitled to have their coats of arms (Blome began his career as a heraldic painter) engraved on a map of their choice.

His map of Leicestershire is dedicated to Theophilus Hastings (1650-1701), 7th Earl of Huntingdon, a scion of one of what had been one of the most powerful landowning families in the county. The family fortunes had suffered during the turbulent decades of the Civil Wars and those of the 7th Earl would fare little better (he had a knack of backing the wrong horse, switching from attempting to have James II excluded from the royal succession to becoming an avowed Jacobite at just the wrong time, one of just 30 people excluded from William III’s 1690 Act of Grace). One can appreciate how, as a young man, he might have leapt at the chance to have his coat of arms on a new map of ‘his’ county as a step towards reasserting his family’s influence.

The commercial element was not always so blatant. In 1677 the fledgling Oxford University Press published Robert Plot’s groundbreaking ‘Natural History of Oxfordshire’, which embodied a new spirit of scientific enquiry. It contains the first printed depiction of a dinosaur bone. Plot didn’t get it quite right: having dismissed the idea that his ‘petrified’ thigh bone was a naturally formed rock which just happened to look like a bone, or had belonged to a Roman elephant, he suggested instead that it was the bone of a giant. The plates are dedicated to various figures, many of them local landowners so that Plot was able to say that at least some of the items illustrated had been found in their grounds. But the most impressive illustration in the book is the large folding map of Oxfordshire, surveyed and drawn by Plot himself, engraved by Michael Burghers and dedicated to John Fell, who had recently become Bishop of Oxford. Today Fell is best remembered for an off the cuff translation of one of Martial’s epigrams, ‘I do not love thee, Dr Fell’, which one of his students extemporised to avoid being sent down. Both Plot and Burghers had every reason to feel indebted to him, as Fell’s patronage and drive established the Oxford University Press as publishers of illustrated and scientific books such as this one. Fell encouraged Plot in his travels and research and on the strength of this book Plot was rapidly elevated to fellowship of the Royal Society and became the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. Fell encouraged Dutch and Dutch-trained engravers such as Burghers to settle in Oxford, and in a remunerative career with the university press spanning half a century Burghers came to be regarded as the best general engraver in England. The map is bordered by 176 coats of arms of Oxford colleges, towns and local members of the nobility and gentry, but Fell full deserves to take centre stage in the dedication.

Looking across the North Sea to Golden Age Amsterdam, one sees a similar range of factors at work. The Blaeu firm’s second map of Brazil, first published in 1642 – contemporary with the rise of the Dutch West India Company and displaying significantly more coastal detail than its predecessor – was dedicated to Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592-1656), a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman who served as a general of artillery for the Netherlands and, from 1637, as a vice-governor of Dutch Brazil. Blaeu praises his efforts as chief of the Dutch military forces in the colony. Over the course of the 1630s the Dutch captured most of northern Brazil from the Portuguese, but began to lose ground in the later 1640s, being finally expelled in 1654. Could Arciszewski have conferred significant patronage on Blaeu? Arciszewski was well connected and led a remarkably colourful life (exile, spy, soldier, pioneering diver, ethnographer…) but I suspect that associating the map with successful Dutch expansion in the region appealed to Blaeu’s customer base. In this context Arciszewski’s name probably helped sell maps.

That’s at least three good reasons for dedications on maps: hard cash in return for an ego boost; gratitude for patronage received and hopes for more to come; associating powerful or relevant figures with maps to boost sales. Those odd little shields and dedications repay a second glance.

Leave a comment