Charles Pearson and the origins of the Met, the world’s first underground railway

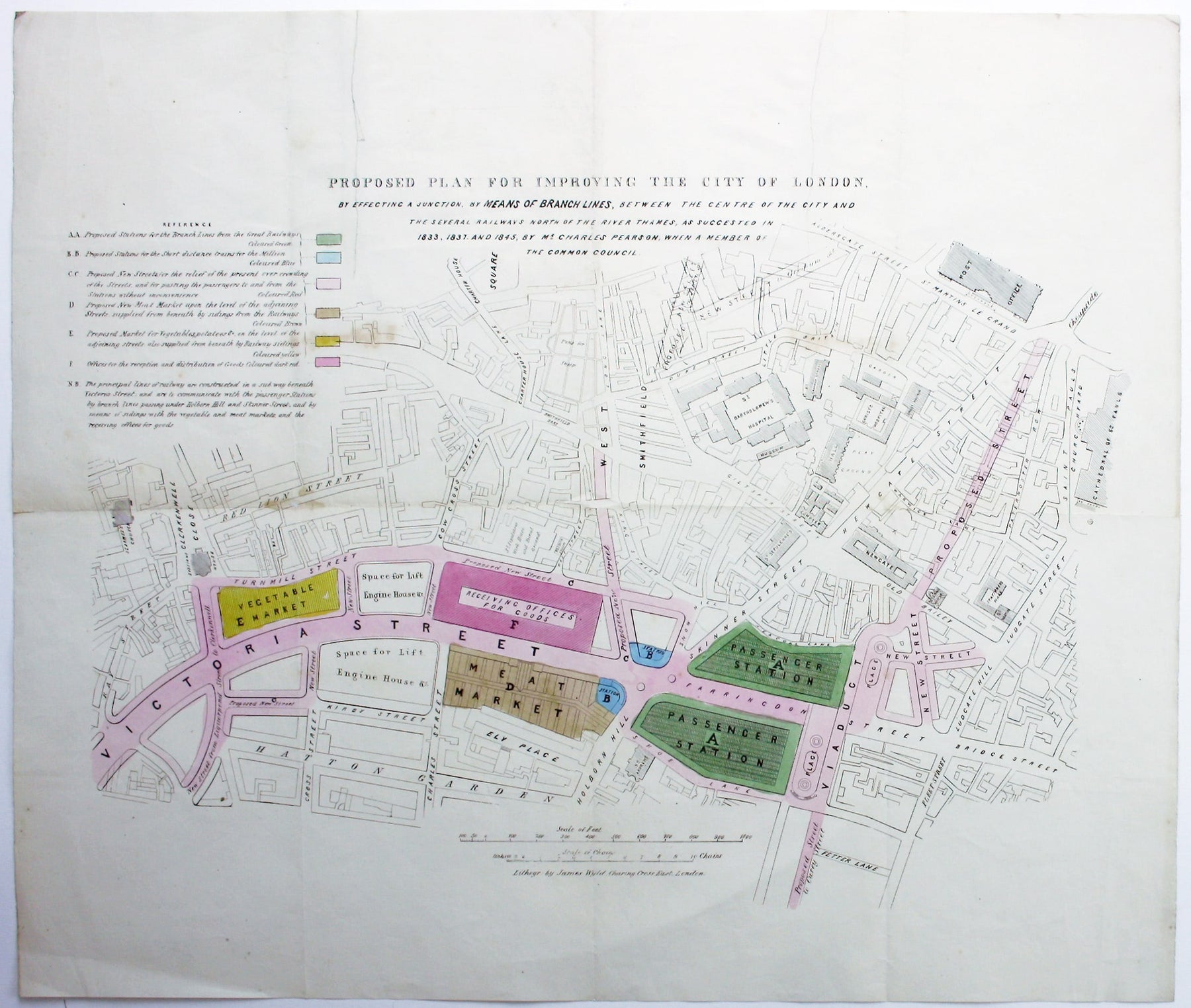

We’re currently piecing together the story behind a scarce map which illuminates the origins of the London Underground. If you’ve seen it before and have further information about the context in which is was published or circulated we’d love to hear from you. Published circa 1850 it shows a huge railway terminus at Farringdon, part of a scheme energetically promoted by Charles Pearson which never came into being in this form. However, Pearson was instrumental in ensuring that the site would eventually become the eastern terminus of the Metropolitan Railway. Opened in January 1863, the Met was London’s first underground line, and indeed the world’s first passenger-carrying underground railway.

Charles Pearson has been credited with being the first to propose an underground railway to ease the traffic congestion caused by London’s rapid growth. He died in September 1862, a matter of months before the Met opened, and without Pearson’s tenacious lobbying and fundraising efforts over a thirty year period – making full use of his position as Solicitor to the City of London – it is unlikely that it would have opened when it did. This rare map seems to have formed part of Pearson’s decades long campaign.

Proposed plan for improving the City of London, by effecting a junction, by means of branch lines, between the centre of the City and the several railways north of the Thames, as suggested in 1833, 1837 and 1845 by Mr Charles Pearson when a member of the Common Council. Lithographed street plan published by James Wyld, sheet size 49 x 57 cm, original hand colour, blank verso.

Proposed plan for improving the City of London, by effecting a junction, by means of branch lines, between the centre of the City and the several railways north of the Thames, as suggested in 1833, 1837 and 1845 by Mr Charles Pearson when a member of the Common Council. Lithographed street plan published by James Wyld, sheet size 49 x 57 cm, original hand colour, blank verso.We have only been able to locate a single institutional example, held by the British Library (OCLC 556390825). Ours has been folded, but there is no indication that it was issued with any of Pearson’s pamphlets on the subject, such as City Improvements (1853). Two panels on the verso are a little dusty, as if they have acted as the map’s covers for a long time, suggesting it was separately issued. It has much in common with maps issued with Parliamentary papers, but it seems more likely that Pearson personally commissioned the map from the younger James Wyld; Wyld was one of the leading London mapmakers of the day and was no stranger to campaigning and controversy himself, often displaying a flair for showmanship. It is a good quality map requiring the correct application of half a dozen different colours and, without further information to go on at this stage, it seems reasonable to assume that Pearson intended to circulate copies among a fairly limited circle of potential supporters.

Pearson had calculated the prohibitive cost of demolishing London yard by yard, in order to build railways above ground. His elegant solution was to build cut-and-cover tunnels beneath new or improved roads, such as Victoria Street on our map. Incidentally, the legend refers to the railway being carried in a ‘sub way’, and OED connects Pearson with the earliest use of subway in the context of underground railways, giving the date 1851. Pearson’s goal was to link the east end and city with the mainline services which stopped short at the periphery of the built up area. As well as commuters and other human passengers he wanted to move fresh produce, and the meat and vegetable markets on our map were an integral part of his thinking.

It differs somewhat from the black and white woodcut plan printed in the May 23 1846 edition of the Illustrated London News, which specifies two underground tunnels feeding a huge terminus at Farringdon, with space to serve up to four railway companies, and with goods stations just outside the main passenger station. On our map the tunnels are not shown, the platforms for the different railway companies (lettered A-D on the ILN plan) are not specified, and there is far greater detail of the facilities on the surface. Had it been built, this iteration of the scheme would have been an atmospheric railway using compressed air to push trains through tunnels, but the 1846 Royal Commission on Metropolitan Railway Termini rejected the plans.

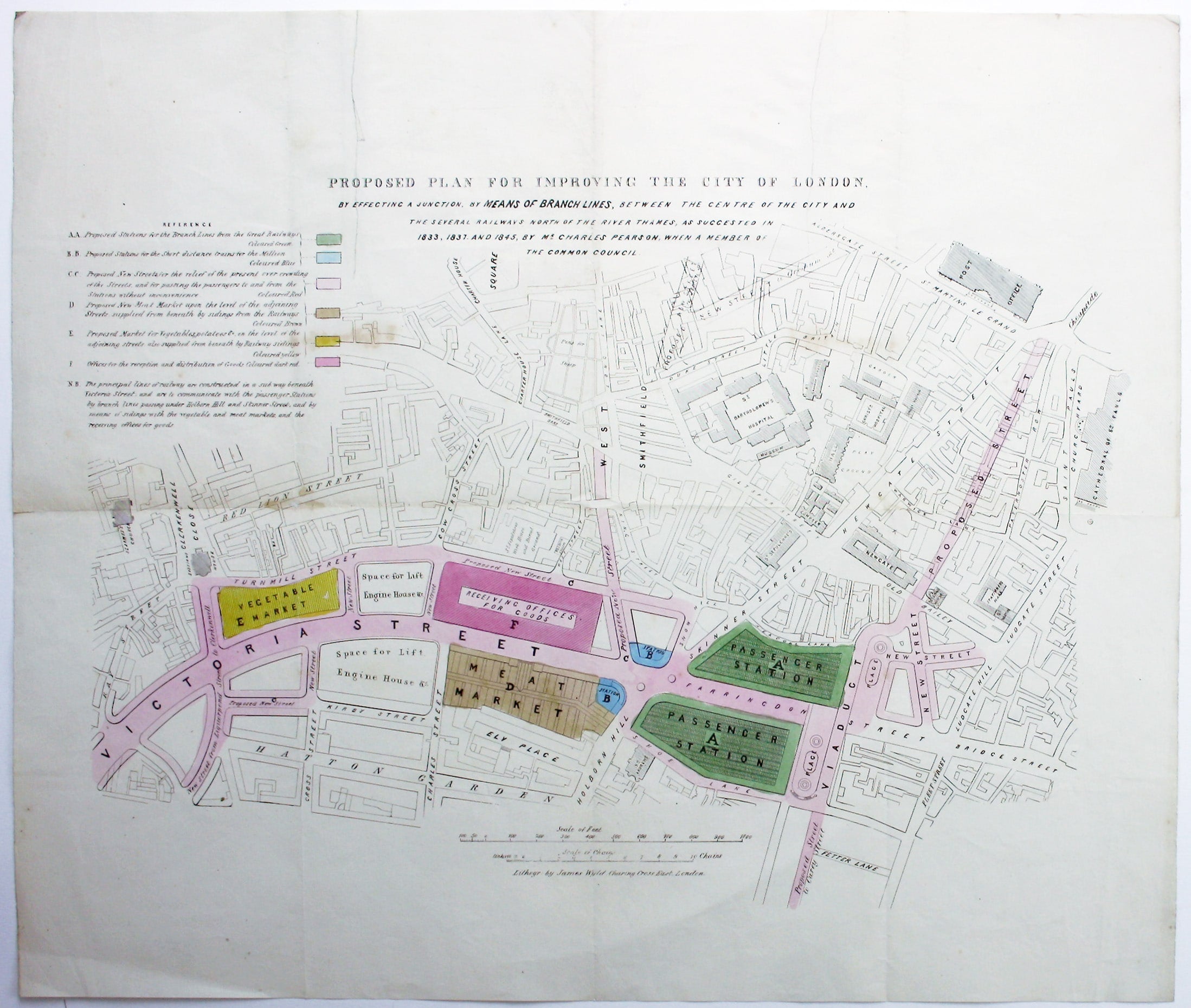

This cartographic puzzle, published thirty years after the Met opened, plays on the congestion that still plagued the capital at the end of the century in spite of Pearson’s efforts. Although the frustrated travellers here are on horseback rather than in cars, it seems that London’s utility companies have never managed to co-ordinate their holes in the road.

The Labyrinth of London. A Puzzle suggested by the numerous Obstacles occasionally presented to the route of the Equestrian through the Metropolis by the Repair of the Roads, Water-pipes, Gas-pipes &c. London, George Newnes, c. 1895. A wood engraving published in ‘The Picture Magazine’.

The Labyrinth of London. A Puzzle suggested by the numerous Obstacles occasionally presented to the route of the Equestrian through the Metropolis by the Repair of the Roads, Water-pipes, Gas-pipes &c. London, George Newnes, c. 1895. A wood engraving published in ‘The Picture Magazine’.Beneath the map is the explanation of how to play: ‘The Traveller is supposed to enter by the Waterloo Road, and his object is to reach St Paul’s Church without passing any of the Barriers which are placed across those Streets supposed to be under Repair’. ‘The Picture Magazine’, was presented as the ‘Companion to the Strand Magazine’ and published 1893-96; COPAC notes that the monthly issues reproduce images typically arranged into the following categories: fine art; portraits; comic pictures; old prints and pictures; autographs; pictures of places, and pictures for children.

Leave a comment