The speeches and writings of MK Gandhi - the earliest anthologies

Gandhi, M.K.: Speeches and Writings authorized up-to-date and comprehensive collection. First edition: G.A. Natesan & Co., Madras <1918>

8vo. pp. xvi, 296,

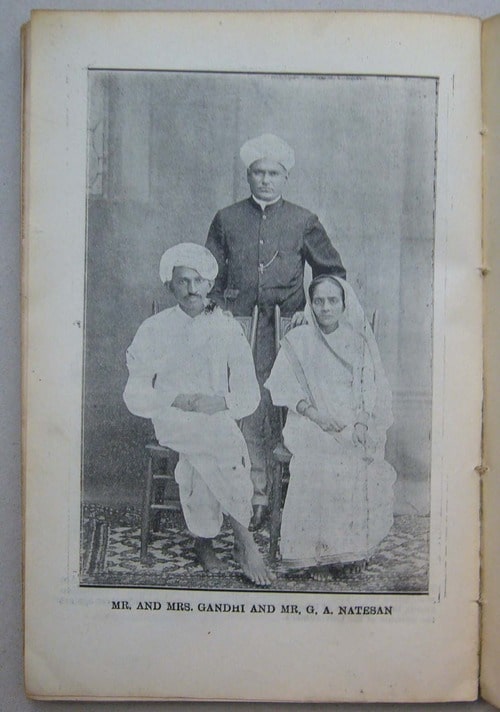

Internal evidence derived from the text and the publisher’s advertisements reveals that this collection was published at the very end of 1917 or early in 1918. Natesan, an Indian nationalist publisher who had sent funds to Gandhi in South Africa and who hosted Gandhi and his wife when they stayed in Madras in 1915, claims in his preface that “this is the first attempt to bring under one cover an authorized, exhaustive and up-to-date collection of the speeches and writings of M.K. Gandhi”. He adds: “the publishers desire to take this opportunity to convey their thanks to Mr Gandhi for the permission accorded to them to bring out this edition of his speeches and writings and for furnishing them with copies of several of his hitherto unpublished speeches as also with English translations of some of his writings and addresses in Guzarati”. Natesan reinforces this sense of Gandhi’s personal involvement with by reproducing a photograph of the author and his wife with the publisher taken in Madras in 1915.

It is a scarce and ephemeral title, with no copies recorded at auction and with only one recorded institutional example of this edition, held by the British Library. However, it marks a critical phase in Gandhi’s thinking. At the 1915 Madras Law Dinner, in the company of his fellow professionals, he proposed the toast to the British Empire, declaring: “the British Empire has certain ideals with which I have fallen in love”, a text which Natesan takes as a preface for this book: In 1917 Gandhi was still actively recruiting Indian troops for frontline service and was committed to the idea of Dominion Status rather than throwing the British out of India, bag and baggage. The events of the immediate postwar period hardened his attitudes and those of his supporters considerably, which may help explain the rarity of Natesan’s original edition.

In 1917 Gandhi was still actively recruiting Indian troops for frontline service and was committed to the idea of Dominion Status rather than throwing the British out of India, bag and baggage. The events of the immediate postwar period hardened his attitudes and those of his supporters considerably, which may help explain the rarity of Natesan’s original edition.

The question of whether or not this is the first ever collected edition of Gandhi’s works is complicated by the existence of another work which was also published in Madras and which has been tentatively dated to 1917 by a library cataloguer - and which again is recorded in only one example. Fortunately both books are in the British Library, making it straightforward to compare them side by side. The volume published by Ganesh & Co under the title Mahatma Gandhi, his life, writings and speeches is a very different work: the collation (pp. lxviii, 288) includes an extensive introduction and account of Gandhi’s life by Mrs Sarojini Naidu, the future leader of the INC, but there is no attempt to suggest a direct link with Gandhi. It is effectively a well-intentioned pirate edition, and establishing primacy is almost impossible. The British Library copy has been rebound without wrappers or advertisements, but the foreword is dated 22nd November 1917, giving a terminus post quam, and the most recent work appears to relate to the Gujarat Educational Congress held on October 20th 1917. Publication in December would be possible. The most recent work in Natesan’s collection is also from November 1917. The publisher’s advertisements cover works published in 1917 (the second edition of Besant’s speeches for example) and a few works - but not many – which have been ascribed to 1918: for example, among the ‘biographies of eminent Indians’ series, the only volume advertised which may belong to 1918 is the life of M.G. Ranade, which serves to reinforce dating of late 1917 or very early 1918.

It is worth exploring this in some detail as the last scholarly investigation of this topic appears to be Stephen Hay’sAnthologies compiled from the writings, speeches, letters, and recorded conversations of M.K. Gandhi (Journal of the American Oriental Society 110.4, 1990). Hay noted: “Madras publishers took the initiative in assembling Gandhi anthologies. The earliest, as far as I can discover, was Mahatma Gandhi: His Life, Writings and Speeches (Madras: Ganesh & Co., 1917; rev. ed. 1918, 436 pp.; 3rd ed., 1921, 444. pp.) … In 1922, another Madras publisher apparently bought the rights to this book and offered a much enlarged third edition under the title, Speeches and writings of Mahatma Gandhi (Natesan, 64, 848, and 64 pp., with index)”. The lack of a collation for the 1917 Ganesh edition suggests that Hay (located in California) had not personally examined the book, and he is only half right at best. Natesan probably had a better claim than Ganesh & Co to intimacy with Gandhi’s circle. His work is better organised (thematically rather than chronologically), contains fresh material, is even printed on better paper stock, and is certainly roughly contemporary with the first Ganesh edition: he did not buy the rights (though quite how that would have worked is uncertain) five years later. It is possible to read into his emphasis on printing an up-to-date- authorised edition a certain annoyance that another publisher had pipped him to the post with (what he considered to be) an inferior collection, but that is pure conjecture.

It is worth noting that both publishers called on the services of the Modern Printing Works of Mount Road, Madras: pp. 273-288 (the index) of the Ganesh edition and pp. 145-296 (about half the text, beginning ‘The Duties of British Citizenship’) of Natesan’s were contracted out. As the content is so different this should be taken an indication that small publishing houses needed to call on outside help rather than evidence of collaboration: a similar book published under different imprints.

Natesan went on to publish a second edition in 1918, expanded to 480 pages (copies in the British Library and the Hesborough Library, University of Notre Dame, as well as a copy incorrectly catalogued under the date 1917 in Denmark). The British Library also holds expanded editions of the Ganesh edition, probably from 1918, with pp. 420 and 436 respectively, and an edition with pp. 444 is held in the Bogazici University Library, Istanbul and libraries in Minnesota, California and Utah. The two nationalist publishers continued to go head to head with their different collections well into the 1920s.

Leave a comment