Isaac Newton And The Buy-6-get-1-free Offer

An Interesting Book With An Interesting Pedigree

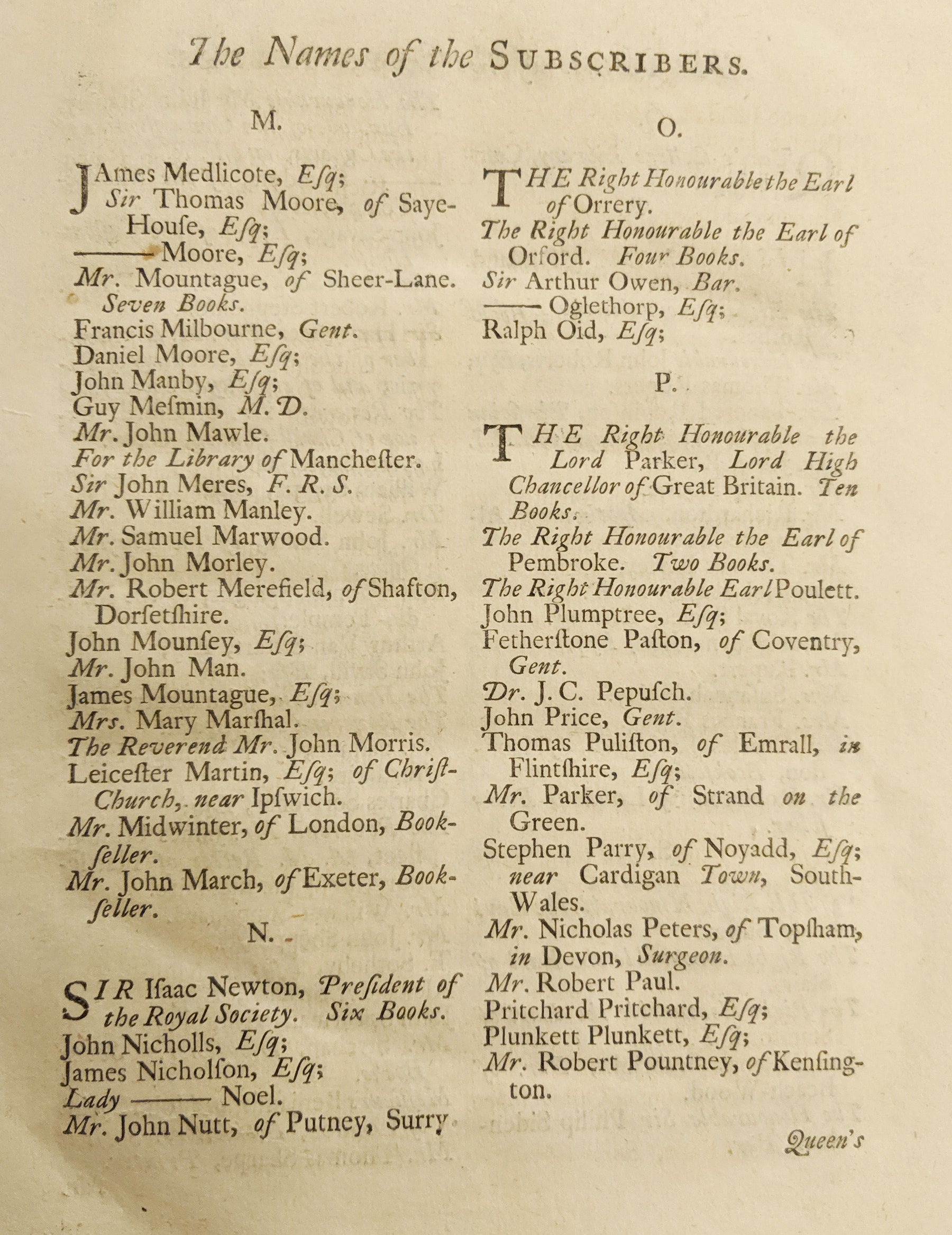

My enthusiasm for poring over lists of subscribers is probably almost as great as that of the original subscribers themselves. I am currently pondering what prompted Sir Isaac Newton to splash out on six copies of Richard Bradley’s ‘A philosophical account of the works of nature’, published by William Mears in 1721. It is certainly an interesting work. The text is wide ranging, dealing with Bradley’s long established interests in agricultural practice and gardening, as well as a coherent attempt to define and describe the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms. The plates are suitably varied, from corals and cacti to a comparison between the skeletons of a human and a monkey, and they are well executed: in the year of publication James Cole became engraver to the Bank of England. But still, six copies? The fact is recorded in black and white in the 8 page list of subscribers at the front of the book: Sir Isaac, then President of the Royal Society, heads the N’s, followed by the number of books he bought.

The rise of crowdfunding and part-publishing

The dedicatee, the Earl of Orrery, was put down for a single copy, somewhat eclipsed by his fellow peers the Dukes of Chandos and Rutland who subscribed for 10 copies apiece, and the Earl of Orford who managed four. Sir John Anstruther and the controversial apothecary Sir John Colebatch put everyone in the shade with 25 books each, narrowly (diplomatically?) followed by a member of the book trade, William Taylor, with 24. Cornelius Crownfield, publisher of the second edition of Newton’s ‘Principia’ at the Cambridge University Press, purchased a respectable 12; booksellers Daniel Browne Robert Gosling, Mr Tooke (Benjamin or Samuel?) and Thomas Woodward all bought 7, as did Thomas Fairchild, ‘Nurseryman at Hoxton’, the pioneering gardener who was the first to scientifically produce an artificial hybrid plant and helped to establish the existence of sex in plants.

Bradley and Fairchild were friends; he is mentioned by name on page 41, and crops up with regularity in Bradley’s other works, such as his ‘General Treatise on Husbandry and Gardening’, published in parts 1721-23, where he lists the flowers blooming in Fairchild’s garden month by month. Through the list of subscribers we also know that Bradley’s book sat on the shelves of other distinguished fellows of the Royal Society including Sir Hans Sloane (items Bradley had seen in Sloane’s collections also rate several mentions) and Sir Christopher Wren. Before exploring the motives of our subscribers further, it might be worthwhile saying a little bit about publishing by subscription. Printing in the hand-press era was a horrifyingly expensive and risky business and the history of the book is littered with bankrupt publishers and booksellers. Anything which could bring money in up front to offset the costs of printing was a bonus. It became popular in the late 17th century, a sort of early modern crowdfunding, at about the same time as publishing particularly expensive or extensive works in parts or instalments also became popular – and for much the same reasons. Through the 18th and into the 19th century printed material including Richard Horwood’s 32 sheet map of London (the largest map published in the UK to that point), John Gould’s magnificently illustrated books of birds and the novels of Charles Dickens were all published in parts. The publisher got a chunk of money back before moving on to the next bit, and the purchaser was able to spread the cost.

Early adopters and a place in posterity

Subscription and part-work publishing were not necessarily mutually exclusive, but there were differences. Subscribers typically stumped up half in advance and half on receipt of the book (as was the case here), and occasionally received a fancier copy than ordinary purchasers, with extra illustrations for example. But the main draw, one suspects, was that they got to have their names associated with the book for posterity. Lists of subscribers are sometimes headed by the most illustrious (often used by the publisher as a lure) but then names are arranged in a pleasingly egalitarian manner, alphabetically or even in the order received, so that in our book by Bradley, Sir Isaac Newton is followed by one John Nicholls Esq.

One can imagine the eagerness with which the finished book might have been received in some households, maybe casually left open to reveal the owner’s name among the great and the good, fellow patrons of the arts and sciences. From a collector’s point of view subscribers’ own copies can attract a premium, but browsing the lists of subscribers and teasing out the connections is a joy in itself. For example, as well as Newton the subscribers here include Cornelius Crownfield and Richard Bentley. Crownfield’s connection with Newton has been mentioned above and Bentley, a brilliant editor of Horace, was also responsible for bringing that second edition of the ‘Principia’ to the press (and he reaped the profit; Newton simply received half a dozen free copies). Lists of subscribers often reveal networks of friends, acquaintances, patrons and colleagues whose orbits circled one another.

Isaac Newton, a good friend and bargain-hunter

Back to Newton and his half dozen copies. One for home, one for the office and the rest for Christmas presents? Why so many? Bradley was appointed the first professor of botany at the University of Cambridge in 1724, but before and after he largely supported himself through his writing. It was a subject for satirical attacks (for example by his successor at Cambridge, John Martyn) and Newton would have known this. For the trade buyers of multiple copies there may have been an element of prestige (being seen to be major buyers, with a thriving customer base). For private buyers the age-old desire to see and be seen may also have been mixed with a genuine desire to support the author.

The publisher William Mears’ approach to soliciting subscriptions in the press – including offering a seventh copy free to anyone who bought six (including Newton), recording their names for posterity in the finished volume and promising not to print more than were subscribed for – has recently been described by Jeffrey Wigelsworth (Selling Science in the Age of Newton, 2016), using the present work as an example. So there we have it, apart from everything else thrifty Sir Isaac received a free copy. The advertised price was 30 shillings which in real terms today (using measuringworth.com) is anything between £220 (retail price index) or a more realistic £3000 (against average earnings – a good indicator of the buying power needed to purchase a book of this calibre). Seen in those terms Mears’ special offer is remarkably generous, and an order from a private individual for 25 copies becomes truly extraordinary. I have a feeling that we will be returning to lists of subscribers in future.

Leave a comment